Speaking with Peter Robb about M

You approach Caravaggio's art very differently from academic art historians, and you have a lot to say about the connections of culture and politics at the time M was painting.

We can't leave art to the professional art historians. On the whole they're prisoners of their training and unlikely to give you any sense of why art matters. They see art as an expression of prevailing values. They look at a religious painting and see theology, official values, precedent, iconology, almost anything but art. Not much on whether the painting lives for looking at it, or how it lives. The language of the discipline struggles to distinguish hackwork from genius. The academics know this, and their descriptions are guarded, timid, inert. Writing on M, they manage to make his paintings sound like all the inferior work of the age instead of proclaiming its amazing newness and difference. There are brilliant exceptions, but art historians mostly write for each other. I'm trying to write for and about real people in the real world. That means widening your field of vision beyond the specialized milieu of art.

I don't do anything particularly original in M. I do give a lot of space to the paintings themselves because they're the best evidence we have of the kind of man M was. The work of any artist is a kind of autobiography, and you have to learn to read it. Anyone who looks at M's paintings feels immediately that this painter was making something intensely personal and original out of the conventional religious subjects he was required to paint. This inner life story running through the paintings would be just as significant even if the rest of the record were less skimpy and mysterious. As it is, the paintings are all we have to make sense of the meager and baffling records of M's life in society. And if you're going to write about an artist, I think you ought to put yourself on the line, say why these paintings matter to you. Unacademically. I'm trying to do that when I describe M's work.

The other thing you can do is look at the time and place in which a work is created, try to get some sense of the whole picture – the look and feel and taste of the palaces and streets, the food, the sex, the clothes as well as the books, the politics, the ideas, the wars and crimes going on at the time. A painter like M was in an extraordinary position, living poised between two worlds. He knew the low life, the streets and taverns and brothels from the early days of struggle. Then, as Cardinal Del Monte's protégé, he knew intimately the immensely refined life of a powerful diplomat, a widely connected intellectual with highly developed interests in art and science. M lived with his young painter friend Mario in Del Monte's palace, where Galileo often stayed, a palace frequented by advanced thinkers and the church's power elite. He painted the Pope but he remained most at home in the street world of his first years as a painter. As a famous painter he was uniquely and intimately in contact with the extremes of society. The only other people who had the same privileged contact with both high and low were his friends and models: the high class courtesans, working girls who became the mistresses of princes and cardinals. You have to keep all this in mind when you write about him.

How do you think M's art was affected by the time he lived in, the crisis in Europe, and the revival of the Inquisition in Italy?

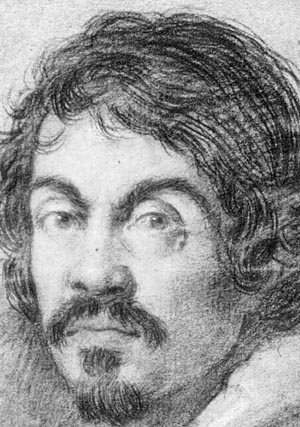

M, of course, is the painter commonly known as Caravaggio, after his hometown near Milan. I call him and the book by this initial because I see his identity as a puzzle, a blank to be filled in by diverse means. The fact that he left so few records of his private life behind him has everything to do with the climate he lived in.

When I was reading about the society M was born into, in the latter part of the sixteenth century, it struck me as remarkably like the cold war Europe that ended quite recently when the Berlin wall came down. There was an iron curtain dividing the continent in the sixteenth century too, separating the Catholic south from the Protestant north. Europe was split in two, ideologically and politically, and sometimes by open war, as when Catholic Spain tried a naval invasion of Protestant England or the Netherlands Protestants rebelled against Spanish rule.

M grew up in Spanish controlled Milan during the most intense phase of the Catholic counter-offensive against Protestant ideas. It was a time when people's ideas and behavior were closely policed by the Inquisition. Art was the main vehicle for religious propaganda and ideological correctness was art's prime requirement. The great generation of the high renaissance artists had gone – Michelangelo had died seven years before M was born, and Titian died when M was five – and when M started painting the established artists were tenth rate time servers. It wasn't a good time to be an innovator. M burst dazzlingly on this scene and he won great acclaim and aroused intense hostility at the same time. Young painters idolized him and copied his style and the art establishment resented his huge success. The religious authorities looked suspiciously on M's very earthly images of the Christian story.

At the same time, I believe his personal life – what a perceptive contemporary called his wildnesses – would have come under disturbing scrutiny. By the time M was famous in Rome, in the opening years of the seventeenth century, the most repressive phase of the church's ideological war was over, but the Inquisition was starting to turn its attention to personal morality and I think there's an almost unspoken subtext of sexual persecution running through M's story. The amazing thing about M is how little the prevailing conformism and repression affected his work. His art or his life. He was utterly intransigent in matters of painting. Technique, image, vision, everything. You might say his greatness came from this unwavering fidelity to his own way of seeing. And that way of seeing, and painting with light, began the line of European art for the next three hundred years or more.

The final years of the 16th century -- and early years of the 17th -- produced some of the greatest thinkers and artists in Europe's history, M among them. Why do you think this was so?

The religious split in Europe and its political consequences were a symptom of a wider intellectual crisis. The best minds were dumping the mental baggage of the past and probing the world with skeptical and objective minds. Shakespeare, Galileo, Cervantes and the philosopher Bruno were all in their different fields questioning received values and placing great value on the way an individual saw the world. M was doing this in art. In the Protestant north, these values fed the middle class revolution and made the modern world. In the Catholic south, reaction triumphed and Italy slid into its long church-ridden decline. Bruno was burnt alive at the start of the century and even the astute Galileo was later condemned by the Inquisition and spent his last years under house arrest. Midway between these two events, more or less, the painter M was hounded to his death. His influence in Italy was fleeting. In Spain, France and the Netherlands his followers formed the avant-garde of modern art. In the culture of the dynamic north you see M's influence, not in his native Italy, which turned instead to the glorious unrealities of the baroque.

How does your M – a revolutionary misfit – differ from other interpretations of the painter?

My book M, if you like, goes back to basics. We know so little about this man. We have so few objective facts. Calling him by his initial M reflects my working procedure as I tried to get a take on this enigmatic painter, so mysterious in the few things we know about his life, so vividly present in his art. I made this initial the book's title because even at the end of what turned out to be a pretty long book I felt I'd made only a beginning in understanding him.

M starts from the early accounts we have of the man, and looks at why his contemporaries called him wild, arrogant, violent, sarcastic, and so on. He was clearly a difficult person, and I look at the very real reasons he had for being difficult, and the reasons a lot of people had for talking him down. But I accept the basic truth of this old image of a socially difficult man who painted in an extraordinary new way, painting directly from life and throwing out both the heavenly fantasies of religious art and the academic practice of working from drawing.

The records that people have been digging up from the criminal archives of Rome and other places have confirmed the reality of a man who even for that time was involved in an unusually large number of very violent episodes. He did, after all, spend the last four years of his life, a quarter of his known painting career, on the run from people who wanted him dead. First he was running from papal justice in Rome and later from an unidentified enemy in Malta as well. I think we owe it to M to consider that this

violence might be related to his painting – to problems his painting and his own artistic intransigence caused him – and not to dismiss him as a man with a talent for trouble, a genius who coincidentally happened to be a murderous psychopath. Because I don't believe he was a psychopath at all. I think he was an extraordinarily, fiercely tenacious man who, in defending his art against its very real enemies, was also defending his sense of himself, including of course his sexual identity and his way of being in the world.

If this differs from current practice, this is because the academy has been taking possession of M's art over the last few decades, centering an immense amount of research and discussion on a painter who not so long ago was still considered a minor and aberrant artist. In doing this, the specialists are following and not leading popular taste. The courses and seminars are there in the universities because the students demand them.

The books are starting to come out because people want to read about him. And since the academy is by its very nature conservative, a lot of its energy has been devoted to pulling M back into the mainstream, and showing that his painterly and religious values weren't so different after all from what everyone else thought about art and religion in M's day. He was really a fairly conventional painter, they say. Orthodox. Even the violence of his daily life, some argue now, was perfectly acceptable for that time. There's this deadening desire to normalize a painter whose life and whose art were both dazzlingly and radically outside established norms. I resist the deadening of a great and living and deeply disturbing painter, and in doing this I am much closer to his own contemporaries in the way I see him.

The Australian Review of Books noted that M "chips away at the inaccuracies, prejudices, and jealousies of the near-contemporary record" of M. How so?

The reviewer was talking about my critical handling of the earliest surviving sources for M's life. The most complete account we have of him comes from a fashionable rival painter M had humiliated and ridiculed years earlier, whose pages on M's life and work are shot through with malice, vindictiveness, and posthumous score settling, not to mention a total failure to understand what M was doing in painting. The most intelligent and influential account was written half a century or so after M's death, by an intellectual who hadn't known him personally and who wanted to demonstrate the wrongness and imitation, as he saw it, of M's way of painting. It was a very subtle demolition job. The man who understood him best, the physician Mancini, who'd known and treated him in Rome, knew next to nothing about M's life before and after the Roman years. A lot of what other people wrote or remembered about M was based on hearsay, most of it ill intentioned. He had, after all, a lot of personal and professional enemies and this inevitably worked its way into the written record. His friends had their reasons for keeping quiet. The account of how he died, which has almost never been questioned, I'm convinced was the covering up of a murder. I explain why in the later chapters of the book. All the early sources need to be sifted through critically. Too many writers on M accept what the early sources say at face value. In fact, they're nearly all deeply suspect.

How does M deal differently than other biographies with the erotic and homoerotic in M's work and life?

One of the weirder aspects of the academic industry that has grown up around M is that the specialists seem to be unaware of the powerful erotic current running through his work. Or at least unwilling to discuss it. For the rest of us, the intensely personal eroticism of M's paintings, combined with the increasingly dark strain of violence and suffering that also runs through them, is what makes his art so immediately gripping.

You'd have to be an academic to miss it. I think probably not all academics do, but the fact that the most voluptuous images are of boys instead of girls probably makes the sex a little hard to handle in the seminar room. The sexual embarrassment is particularly intense in Italy, a country where anything goes as long as it's in private and unmentioned and where the most useful research into M's life otherwise gets done. There are some fascinating and strongly individual women and girls in M's paintings too, though the visual interest is more in their strength or pathos. I think M's life included heterosexual activity and attachment, but his feeling for boys was far stronger and his paintings clearly reflect this.

The reluctance of the specialists to talk about this doesn't help an understanding of M's life much. In fact, the paintings have great documentary value here, since his friends and lovers were often also his models. We can identify his most striking female models as two well known Roman courtesans, one certainly and the other almost surely. His two much painted boy models are his young friend and maybe lover Mario Minniti and his young lover and assistant Cecco Boneri. Both of them were with M for years, and both became well known painters themselves after his death. These identifications of his models link with further rich veins of information and hypothesis about the circumstances of M's life and the kind of man he was.

You discard the generally held belief that M died of a fever, suggesting a much more sinister death. Can you tell us about that?

The universally accepted version of M's death comes from his first biographer, who said that when M was on his way back to Rome from Naples in the summer of 1610, having been promised a pardon by the Pope, he was mistakenly arrested at a coastal garrison. When he was released a day or so later he found that the boat he was travelling on had left him and taken his stuff, which included a couple of paintings he was taking as a crucial peace offering for the Pope's art-collecting cardinal nephew. In this account, M tried to overtake the boat by following it up the coast on foot, until he had an attack of fever and died. Nobody seems to have questioned this story until my friend Vincenzo Pacelli expressed some perplexities at a conference in Rome in 1995. He pointed out some of its gaps and improbabilities and contradictions and raised the question of foul play. I was very interested in what he had to say, but when I was doing the rounds in the course of researching my book, everyone dismissed the idea and so, provisionally, did I.

But when I got into the enigmas of M's arrest and imprisonment in Malta, his dramatic escape, his life on the run in Sicily, the near fatal attack on him the moment he got back to Naples, and the things that happened immediately after he disappeared on the way back to Rome, I found that by linking these events, looking at common threads running through them, discarding the impossibilities that Pacelli had drawn attention to, everything fell into place in a compelling hypothesis that developed in the face of my own expectations. As an hypothesis, it links and explains the unexplained arrest in Malta, the strange fear in Sicily, the murderous attack in Naples and the remote death on the way to Rome. It explains the silences in the official record.

I think M, at the height of his acclaim and official honor as a knight of Malta, was jailed for unmentionable sex with a boy, pursued for this by some offended party – a rival or relative among the knights – and eventually ambushed and killed with the possible connivance of both his aristocratic protectors and the papacy, maybe through the influence of his enemy or because the offence was held to be heinous and M himself to be a liability. This version fits all the known facts, it disposes of the absurdities of the standard account and suggests how that story came about, as a partly true cover-up of the murder. If other evidence turns up, I'll rethink it, but until then I'll go on feeling exhilarated at having made sense of a series of otherwise random and incomprehensible events. There were a lot of elements in play in this story. It's something you have to read about in the book.

You have a long-standing passion for Italy. What draws you to this country, and how has it impacted your own writing?

What drew me to Italy, specifically southern Italy, and the Mediterranean countries and cultures in general, was a sense I'd had since I was very young that these countries and peoples were richest in the qualities my own anglophone culture was poorest in. The visual, the plastic, the musical, the physical, the erotic, the culinary, a sense of continuity with the past. All these things, and people's resources of emotional intensity, seemed to me marvelous compared with Anglo calculation and control. And it was all true. The trouble was, I was arriving at the very end of an ancient culture. These days I don't find so much difference any more. The English-speaking peoples have loosened up, learned to learn from the minority cultures living among them, and the Italians have become late capitalist consumers like everyone else.

In the fourteen years I lived in Italy, I gradually realized that the personal resourcefulness I admired in people there wasn't just a personal grace but something needed to deal with terrible failings in the body politic, failings that didn't seem to me marvelous at all. Like everyone else, I guess, I'm still baffled by the intricacies of the connections between what's wonderful and what's truly dreadful in contemporary Italy. If I hadn't felt the need to make sense of this experience, I probably wouldn't have started writing at all. It turned my mind to the Italian past as well. In that sense M grows out of my first book, Midnight in Sicily.

In Midnight in Sicily, you wrote in detail about political corruption in contemporary Italy, but this wasn't the first time you tackled police or governmental corruption. Tell us a little about your earlier experiences in Sydney?

After coming back to Australia and before I went off again on my long Italian parenthesis in the late nineteen seventies, I lived among Italian migrants in an old corner of inner Sydney, just down from police headquarters. I taught English language to newly arrived migrants in various situations and one of these for a while was Long Bay Jail. I also taught illiterate Australian prisoners to read and write in the same classes, and during the lessons I started hearing about a prisoner who was currently on the run. Other prisoners told me he was sure to be killed, because he was unable to pay the detectives who'd arranged his release.

When the prisoner was indeed killed, in a particularly gross police stakeout a couple of days later, I started probing the things that lay behind the killing, and writing about the activities of a group of corrupt detectives in the Sydney police. I became aware of a quite horrifying underside of criminality and corruption in Sydney, and I realized toward the end that only the fact that my identity was unknown, since I wrote under another name, had stopped me from being killed. The police had a contract out on the writer of the articles and at one point my car was shot at, I think in warning. My cover was blown definitively when I was called as a defense witness in a bank robbery trial, and although the state attorney general intervened to protect me from the state police, I never really felt comfortable in Sydney. A lid was put on police corruption.

Not long after that I left Australia, heading eventually for South America. My efforts to expose the extent of police corruption in Australia had been a total failure and left me isolated and in some danger. On my way to South America I stopped off in southern Italy, because that part of the world was dear to me, and I ended up staying there fourteen years. It wasn't the best place in the world to get away from criminality and corruption, as I soon started discovering. Years later, I heard that while I was away the Sydney detectives I'd been tracking got out of control and their activities eventually erupted in a series of scandals. If I'd been more successful I might have saved a few lives. I never regained my innocence about the real workings of apparently orderly societies, as you can see in both Midnight in Sicily and M.

![]()

|

|

||||

|

|

Email Duffy and Snellgrove | |||

|

|

||||